Revised 5/2/'99

Dr. Peck was a prominent microbiologist, trained at Wesleyan University (BA and MA) and Case-Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio (PhD) where he was a student of Dr. Howard Gest. On his passing, Dr. Gest said "Harry was my first and most outstanding PhD Student." Dr. Peck was a Foundation Post-doctoral Fellow at Harvard University and the Rockefeller University where he worked with the Nobelist and very famous biochemist Dr. Fritz Lipmann. He then joined the staff of the enzymology group of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in 1958. After a year in Marseilles, France, as a Senior NSF Postdoctoral Fellow collaborating with Dr. J. C. Senez, he was brought to Georgia in 1965 to help form the Biochemistry Department and serve as its first Department Head. Dr. Peck served on the editorial boards of the Journal of Bacteriology and Biochimica et Biophysica Acta and was twice a Foundation for Microbiology Lecturer. In addition to his administrative duties as Department Head, Dr. Peck also served as Acting Chairman of the Biology Division (1978-79); as Director of Research at the Laboratoire d'Bioenergie Solaire Centre Nucleaire de Cadarache, France (1983); and as Director of the School of Chemical Sciences here at UGA (1985-1991).

Dr. Peck's research interests were in microbial

biochemistry and the molecular biology

of anaerobic bacteria. He had broad interests in how the anaerobic sulfate-reducing

bacteria utilize sulfate as their terminal electron acceptor and generate ATP by

electron transfer coupled phosphorylation. The definitive proof that anaerobic,

non-photosynthetic, bacteria are capable of performing oxidative phosphorylations came

out of his 1964 studies with Senez and Jean LeGall, then a member of Senez's staff. The

BBRC paper establishing

this (H. D. Peck, Jr., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 22, 112, 1966) was

later re-published as a Benchmark in Microbiology (Benchmark Papers in Microbiology,

W. P. Hempfling, ed., Vol. 13, Academic Press, 1979). The collaboration with Jean Le Gall

that began in 1964 continued throughout Harry's research career culminating with their

co-editing of the Methods in Enzymology volume (vol 243, 1994) on "Inorganic Microbial

Sulfur Metabolism" to which many of their colleagues and former students contributed.

Harry and his colleagues developed methods for studying the complex multi-cofactor enzymes and electron carriers of these systems. He realized the importance of molecular genetics tools to basic biochemical studies very early and with them pushed the knowledge of sulfate reducing bacteria to a new level. His approach involved a broad range of biochemical, physiological and molecular biological techniques and was directed at generating an integrated overview of the bioenergetics of respiratory sulfate reduction. Lars Ljungdahl, a long time friend and colleague, says that "Harry understood how to be a philosopher of science. He had a wide perspective. In scientific terms he was a very broad minded person." Over his long research career Dr. Peck published over 160 papers. His research was well supported by NSF, NIH and DOE. During the period from 1980 to 1991 grants from various agencies to Dr. Peck and his coworkers exceeded $3.5M.

Dr. Peck was involved at, literally, the very beginnings of the Department of Biochemistry at the University. In his own words ("Ten Year Self Study," 1979):

Modern Biochemistry came to the University of Georgia in 1953 when the Department of Chemistry hired Dr. Robert A. McRorie, who had recently received his Ph. D. from the University of Texas, to come to the University to carry out instructional responsibilities in biochemistry for the School of Veterinary Medicine. By 1961 there were four budgeted positions in the Department of Chemistry allocated to Biochemistry. ...Other than Dr. McRorie [these] included Dr. Milton J. Cormier who had come to the University in 1958 from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Dr. William L. Williams who came to the University in 1959 from private industry; and Dr. John Totter, who joined the faculty in 1961, coming from Oak Ridge National Laboratory. In 1960 Dr. Leon Dure joined Dr. Cormier as a post-doctoral research associate after completing his Ph.D. at the University of Texas.The proposal for a separate Department of Biochemistry (dated January 31, 1964) was crafted by Robert A. McRorie, Milton J. Cormier, William L. Williams and Leon S. Dure, III. They pointed out that UGA was relatively late in following the trend toward separate Biochemistry Departments. Even at that time there was a tremendous growth of Biochemistry as a discipline with "nearly as many Biochemistry (97) as Chemistry Departments (128)." In 1963 the Federated Societies for Experimental Biology meeting-- where over 85 per cent of the membership presented predominantly biochemical papers-- was claimed to be the largest scientific meeting in the world.In 1960, Dr. McRorie became director of the Office of General Research and Dr. Totter left the University in 1963 to assume a staff position with the Atomic Energy Commission in Washington. Dr. Dure accepted appointment as an Assistant Professor in 1962.

..In 1965 the decision was made to form the Department of Biochemistry. Dr. Harry D. Peck, a staff scientist of the Biology Division of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, was hired as Head and the Department of Biochemistry became an autonomous department July 1, 1965 with temporary space.. in the Chemistry and the Pharmacy buildings. Soon afterwards, application was made to the National Science Foundation for matching funds to support the construction of the Biochemistry area of the Graduate Studies Building in July of 1968."

This proposal is an interesting document in the History of the Department in that it summarizes the standing of the discipline at the time and accurately forecasts the growth and importance of the field. Even before the formation of the Department, the biochemists (McRorie, Cormier, Williams and Dure) were attracting significant grant funds (over $200,000 in 1962). Indeed, their proposal leveraged salary savings from grant awards (50% of Dure's salary, 100% of Williams' and a pending award to Cormier) against hiring of three new faculty including a Department Head with a proposed salary of $19,000 per year!

Harry was recruited as the first head of the Department of Biochemistry by Bob McRorie, Dean John Eidson and Jack Payne who later became the Dean of the Franklin College. Jack, who had known Harry at Oak Ridge, McRorie and others realized a good biochemistry program would be a key element in building the biological sciences. Jack remembers that he and the head of the Zoology Department, a fellow named Barclay McGhee, went to Dean Eidson and said that "if we're going to develop the biological sciences then we need a biochemistry department." Dean Eidson replied to Jack, "well then, why don't you be head of a Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology." But Jack told him that that was absolutely the wrong thing to do. "We don't just need people that use biochemistry to study micro-organisms, but we need real biochemists to teach our students to think in those veins, to get that background." So Harry was hired in 1965, but he had already scheduled for a year in France working with Senez. Thus, while he was nominally the new head of the fledgling department, he was in France and did not really begin building the Department until 1966. During the year before he came, Bill Williams and Milt Cormier got at cross purposes with the head of Chemistry, William S. Pelletier, and they wanted to completely separate from chemistry. The Chemistry Head complained to the President, O. C. Aderhold. The President, searching for the best solution, asked the Dean of the Graduate school, Gerald Huff, to find out and advise him. Gerald had Jack, Milt, Leon and maybe Bill Williams come to his house one night and asked them about Biochemistry and whether Harry was prestigious enough to be the head. Jack was able to convince Gerald that Harry had very high standing in his discipline. He was up and coming, and from Case Western which was "the" Biochemistry and Microbiolgy place of the time. He had worked with 1953 Nobel laureate, Fritz Lipmann. He had several years of independent research at Oak Ridge. His major professor, Howard Gest, was considered one of the best microbiologists. They obviously convinced the Dean and the plans for a separate Biochemistry Department prevailed. While the details of the negotiations are lost, the dean's memorandum creating the department gives us some flavor of the issues involved.

A key

element in the early growth of all of the departments of Biological Sciences was a large NSF Center of

Excellence grant which made possible both expansion of the individual departments and substantial

improvements in support services. The NSF center of excellence monies were used well. They resulted

in tremendous growth. They built the fermentation plant, put equipment

in place to support modern research. Jack recalls that the fermentation plant was Harry's idea and he

pushed hard for it. This was probably driven by his experience at Oak Ridge where they had a facility

for cell growth and he knew that if you were going to study microbial enzymes you had to grow tremendous

quantities of cells. The attraction of the Fermentation Plant was one of the major ones for Lars who came

in 1967, one year after Harry actually came. He and Harry were to have their labs in the fermentation plant.

Both the Graduate Studies addition and

the Fermentation Plant were being built at the time, so Lars and Harry shared a desk while things

were being completed. In the meantime, Harry arranged for Lars to go to Oak Ridge and use their

Fermentation plant facilities. Indeed like Jack before and Leon later, Lars was an Oak Ridge

lecturer/fellow for a year. This tie to Oak Ridge National Laboratories and the Biology Division

there was a strong influence and help for the young Department.

A key

element in the early growth of all of the departments of Biological Sciences was a large NSF Center of

Excellence grant which made possible both expansion of the individual departments and substantial

improvements in support services. The NSF center of excellence monies were used well. They resulted

in tremendous growth. They built the fermentation plant, put equipment

in place to support modern research. Jack recalls that the fermentation plant was Harry's idea and he

pushed hard for it. This was probably driven by his experience at Oak Ridge where they had a facility

for cell growth and he knew that if you were going to study microbial enzymes you had to grow tremendous

quantities of cells. The attraction of the Fermentation Plant was one of the major ones for Lars who came

in 1967, one year after Harry actually came. He and Harry were to have their labs in the fermentation plant.

Both the Graduate Studies addition and

the Fermentation Plant were being built at the time, so Lars and Harry shared a desk while things

were being completed. In the meantime, Harry arranged for Lars to go to Oak Ridge and use their

Fermentation plant facilities. Indeed like Jack before and Leon later, Lars was an Oak Ridge

lecturer/fellow for a year. This tie to Oak Ridge National Laboratories and the Biology Division

there was a strong influence and help for the young Department.

In fact the impact of the 'Ridge on science in the South was a direct consequence of the tenure of Alex Hollander there. He had come to Birmingham AL from Germany when he was 19 and had a dedication to improving science education in the southeast. He used the resources of Oak Ridge and the bully pulpit of his position there to further these goals. It might not be obvious to the broad scientific community how extensive the influence of Oak Ridge has been and how many high impact discoveries of early enzymology can be traced there. The developments of modern chromatography have their base at the 'Ridge, directly linked to the War years research in separation science. Waldo Cohn began developing ion exchange chromatography there during the war years and immediately after to separate radioactive isotopes. In 1947 he began work in the Biology Division and used his techniques to separate nucleic acids. He discovered RNA and many other nucleotides. Some would call Cohn the father of modern column chromatography methods. David Novelli's work on DNA was critical to the development and training of many early molecular geneticists. Oak Ridge was key in development of analytical techniques at a critical time in the growth of the field. For scientists in the Southeast, the Oak Ridge connection allowed them access to expensive equipment, to radioactively labeled compounds, to liquid helium, to large scale cell growth and to a source of young, well respected scientists who were "acclimatized" to the south. Harry Peck was one of these.

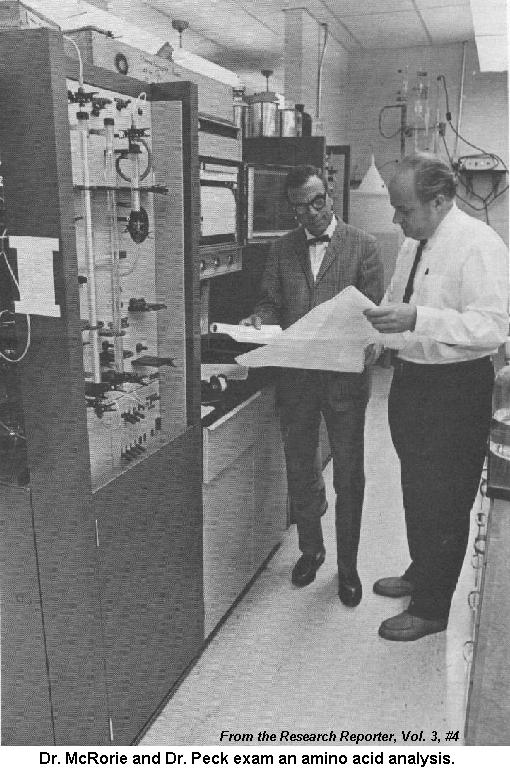

Harry knew the value of good support services. His department was one of the earliest Biochemistry Departments to have large scale support services. Not just the Fermentation Plant, but amino acid analysis, ultracentrifugation, mass spectroscopy and a variety of smaller equipment. The philosophy of Harry and Bob McRorie of building such infrastructure of instrumention and scientific services extends to this day.

McRorie's management of the General Research office was a tremendous aid in the early developments of the Department. Lars recalls:

I remember very well when I came here I went to McRorie and asked for equipment. I wanted to have a Gilford spectrophotometer and McRorie had his accounts of the research money in a notebook in his pocket." You went up to him and said "I'd like to have a Gilford Spectrophotometer" and he'd look at his notebook and say "well how much does that cost". I said "... between 10 and 15 thousand dollars". McRorie say "well, you know Lars, you're not the only one who has to have equipment here. Do you really need it?" So I said "Yes sir!" and he said Lars "Why don't you order it?" I mean thats how it was.Lars Ljungdahl places much of the early success of the Department squarely on the guidence and early decisions of Dr. Peck. He encouraged all of his faculty to aggressively seek external grant funds. Lars remembers when he got his first NIH grant in 1968 for $38,000 that it was written up in the paper and he got telegrams from U.S. Senators Talmadge and Russell. It had hardly been heard of that someone from the University of Georgia could get an NIH grant. The Medical School in Augusta complained. But by 1971 such grants were no longer unusual and the annual grant funds attracted by the Department exceeded $650,000 and topped $1M for the first time in 1972.

Harry realized the problem of attracting and hiring "top gun" biochemists to the new department was compounded by the lack of a track record here at Georgia and no medical school on campus. Lars believes that he actually considered the lack of medical school affiliation as an advantage allowing more freedom to do things and develop research areas without the influence of the medical thinking of the time. And while it might not have been a conscious strategy to hire strong people in more esoteric areas, this was the outcome of much of the early growth. Certainly there was a conscious strategy to hire, in Lars words, the "crowned princes" from the "top guns."

Jim Travis who was a student of Bill McElroy (later head of the National Science Foundation and President of the University of California at ) is an example of one of these hires. Milt Cormier and McElroy knew each other through their time in Oak Ridge and their research interests in Bioluminescence. Jim remembers meeting Harry, Milt and Leon Dure at a Chicago cocktail party. "They were all having a good time and it seemed like a bunch of active people... It was a pretty fast visit to Georgia right after that, and leaving the snow in Maryland to see azaleas and dogwoods in Georgia made the decision to move a lot easier. Indeed, it was a move I never regretted."

Bill Williams who retired in 1984 after a long and successful academic career gives us some feeling for the difficulty of attracting good people to Georgia in the 1960's.

I must admit that I came to UGA simply to get a decent address from which I could apply to for a job at one of the leading Biochemical departments in the U.S. Was I ever in for a surprise at Georgia!! Georgia had been described to me in California as "deathly poor" and "parsimonious" but when McRorie showed me the new Science Center under construction...- the whole Center being paid for ($15,000,000) entirely by Georgia State money-... the more I saw - the more people I met- [I said "]Georgia is the place for me["].Harry also realized how important it was for his fledgling Department to become known, to be in the social and political mix of biochemistry. Milt remembers that one of Harry's cleaver schemes "had to to with the annual meetings of the Federation Society which at the time met every year near the boardwalk area of Atlantic City, N.J. We chartered a plane directly from Athens to Atlantic City in which we took all the faculty and some selected postdocs and graduate students. Harry arranged to stay in a large suite with a sizable living room area. It was there that we held what became known as the "Georgia Party". This was a cocktail party held shortly after the end of the afternoon sessions every day. Word was passed around in the beginning and it was always the duty of the graduate students to purchase the necessary items for the party with funds provided by the faculty. Within a couple of years or so members of the Federation began to ask us "where will the Georgia Party be held?" It was at those parties that we were able to do a lot of very helpful networking. A number of our new faculty were selected at those parties along with good graduate students and postdocs. It was also because of those parties that additions to our faculty were multinational in nature giving the department a unique flavor."

Lars agrees, "We all went the biochemistry meeting at Atlantic City [en mass]. We would hire buses [and later a chartered plane]. I remember there was a restaurant there called McKee's and there would be Harland Wood (from Case Western Reserve) and his group. One time they were there with a whole bunch of other good guys sitting there singing and we came in, the whole bunch from Georgia, and we started to sing too. It became a.. It went back and forth [them singing, then us]. It was fun. Harry liked that. We repeated [this] down in San Francisco once, I remember. It ended up at 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning. It was just plain fun. I think Georgia [had] a reputation that we had those parties and that meant that people came to us and we got good contacts."

It was all done "in an economical way." More extravagant in appearance than fact. For example, in the early '70's on one of our trips to Atlantic City, when Harry found out that John Wampler was driving in order to see his sister in Washington on the way, he talked John into buying all of the liquor supplies for the Georgia Parties in DC before coming over to Atlantic City. He gave him a detailed list and exact change. John who was a bit naive did not realize he was "bootlegging" the cheap, tax free liquor, from Washington into New Jersey!

Harry enjoyed a good party, good food and a good cigar. Jim Travis recalls his favorite party story: "we had a party at my house in Cherokee Forest. We went through 3 kegs of beer (had over 100 people at the house in the basement)...Lillian and I just went to bed at 2:00 a.m. while they were still downstairs. When I got up at 7:00 a.m. Harry was still going strong[!]"

Jim Travis remembers that "Harry and I talked a lot about the department, but his major frustration was lack of recognition. This was tough to overcome, and he was always pleased when one of us got an NIH award, got on an NIH panel, or got on an Editorial Advisory Board. He really thought we needed to develop our own P.R."

As the Department grew in influence both outside and inside the University, Dr. Peck made major contributions to the growth of the Biology Division of the Franklin College. He was a key player in attracting people like Mel Fuller to Botany, Joe Key to the Division Chairmanship (now Vice President for Research), Len Mortenson to the same position after Dr. Key, and Gordon Patel (now Dean of the Graduate School) to Zoology. Early recruits into Biochemistry with research interests in molecular genetics such as Sidney Kushner, Bruce Carlton and Robert Lansman went on to form the Genetics Department in 1980.

During the next decade of the Department's growth,

the hiring and recruitment strategy was modified somewhat. Harry actively

promoted a number of advantageous, "target of opportunity" hirings of senior people.

These efforts were also supported by the University and, in particular, by Dr. Joe

Key's office. While many of these senior people were not recruited specifically

for Biochemistry, it was often the case that they choose the Department for their

academic affiliation bringing even more prestige and resources to the Department.

For example, when Karl-Erik Eriksson was hired as Eminent Scholar of Biotechnology

in November 1988 he chose Biochemistry as his home Department. By the early '80's

the annual extramural grant funds had topped $2M. This increased dramatically

--nearly doubling-- by 1985 as these advantageous hirings brought other large

programs into the Department such as the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center under

the Direction of Dr. Peter Albersheim and the Center for Metalloenzyme Studies formed

by Mortensen and built with the leadership of Michael Johnson, Robert Scott and Mike.

In this latter case many of the major players in the CMS were hired during the period

when Harry was Director of the School of Chemical Sciences and could influence

recruitment for both the Biochemistry and Chemistry Departments.

Indeed, Jack Payne says that the biggest contribution that Harry made to the University was when Jack was Dean. "Chemistry was having trouble keeping a Department Head. Chemistry had a acting head for a couple of years. [They] had a tendency to go to an acting head rather than a permanent one." President Davidson was urging Jack to do something and Jack interviewed some people for the position that were not very satisfactory. Buck Rodgers, a prominent professor in chemistry, had urged Jack at one time to get Harry to be head of both Biochemistry and Chemistry. At the time Jack thought that that would be a disaster. But with the President prompting him to do something, Jack talked with Harry and pointed out that there were four vacancies in Chemistry and how there were already so many people interested in metal enzymes at UGA. So Jack put it to Harry to take over and make a school of the two Departments with him as director and that he could then use those positions to build the metalloenzyme and inorganic biochemistry area. He agreed and when Jack took the idea to the President he gave it his whole-hearted endorsement.

Harry's influence on the Chemistry Department as Director of the School of Chemical Sciences is seen in several areas. In addition to building on the strength of the department in compuational chemistry promoting the recruitment of individuals like Henry F. Schaefer from the University of California at Berkley and Phil Bowen from the University of North Carolina, he took advantage of opportunities to hire some rising young talent in the area of metallobiochemistry. During the a two year period from 1986 to 1987 Don Kurtz, Mike Johnson, and Bob Scott were hired in Chemistry and Mike Adams was hired in Biochemistry. Each of these additions sparked further developments with formation of the Center for Computation Quantum Chemistry (CCQC), the Computational Center for Molecular Structure (CCMSD) and Design and the Center for Metalloenzyme Studies (CMS). The CMS, actually formed by Lenord Mortenson (then chair of the Division of Biological Sciences), greatly benifited from these additions. Mike Johnson joined Len along with Bob Scott to develop a successful NSF training program in Transition Metals in Biology which has established UGA as the pre-eminent center of excellence in the field of inorganic biochemistry. Bob Scott who went on to become the Department Head of Chemistry says "Harry's strategic hires quickly turned the tide for the Chemistry Department, making the School of Chemical Sciences obsolete within a few short years. Although at the time, faculty in the Chemistry Department were concerned about the establishment of the School, in retrospect virtually everyone in the Department looks back at this time as one of rapid growth and renewal for what is now a very healthy, research-active Department."

The Biochemistry Department which began in borrowed space in Chemistry and Pharmacy buildings quickly outgrew the space built for it atop the Graduate Studies Building-- a space designed to house six faculty and their research programs- even before it was occupied in 1967. For example, when Lars joined the University in 1967, he "was assigned a space of half a desk in the Chemistry Department" and eventually "was given a laboratory in a former car repair shop converted to the fermentation plant." By the late '70's the 19 faculty of the Department were housed in six different buildings and seven tenured faculty had no office typically using a desk in a corner of their labs as office space. In 1978 Dr. Peck asked a committee (Dr.s Cormier, Dure, and Ljungdalh from Biochemistry along with Dr.s Giles and Kushner from Genetics) to lobby the upper administration for support for a new building to house the two departments and promote the development of biotechnology at UGA. This committee met with UGA President Fred Davidson and quickly obtained his support. Not so quickly and only after dogged efforts by Dr. Peck, President Davidson, Dr. Kushner and many others in both departments, ground breaking for the new Life Sciences building took place in 1987 (see History of Life Sciences Building).

The Biochemists have played major, driving roles in obtaining their research space through out their history. When the new Chemistry Building was completed in 1960, the biochemists applied for NSF monies to finish some of the uncompleted parts of the building for their use. The Department's space in the Graduate studies building (occupied in 1968) was partially paid for by NSF funds ($333,000) raised to match the state's outlay.

The Biochemists have played major, driving roles in obtaining their research space through out their history. When the new Chemistry Building was completed in 1960, the biochemists applied for NSF monies to finish some of the uncompleted parts of the building for their use. The Department's space in the Graduate studies building (occupied in 1968) was partially paid for by NSF funds ($333,000) raised to match the state's outlay.

The support of President Davidson was critical to the eventual success of the drive for the Life Sciences Building. Davidson's support, in turn, was the result of long and successful lobbying and political efforts by Harry Peck. The "rescue" of the Chemistry Department described above and a variety of other opportunistic decisions and involvement's had built considerable political capital. One example, which President Davidson often cited, was the vote of the Department's faculty in 1975 to offer up their 1975-76 raises to help fund programs damaged by state cutbacks. In proposing this to the faculty Harry saw the political benefit and argued successfully for their full support. The Athens Banner Herald article (December 21, 1975) clearly shows what a powerful statement was made by this vote. Its importance is underlined by the fact "the Department was the only group at the University to make this offer."

As Milt Cormier once said, "Harry hired good people and kept them happy." Of the 42 faculty either present at the inception of the Department or hired during the 26 year tenure of Harry Peck, only two left due to failure to achieve tenure and only 7 left for other positions elsewhere in academics or business. Three of the early members of the department left to form the Genetics Department, eight have become involved in the upper administration of the University and seven have retired after long and productive careers. Instead of leaving as their success brought them more prestige, many people have stayed in Athens to build substantial research programs and to grow to be leaders in their fields. Dr. Ljungdahl, hired in 1967, formed the Center for Biological Resource Recovery and the Georgia Research Alliance Biotechnology Center, both housed in the Department. Dr. Dure, "on-board" from the Department's inception, heads the International Society for Plant Molecular Biology. The editorial offices of several journals have been located within the Department. By the early 1990's, the external grant awards had grown to over $7M and the department had lead the Franklin College in research funding for 21 consecutive years. The faculty were publishing well over 200 research publications annually and presenting their work in over 100 National and International Meeting each year. The undergraduate majors in Biochemistry topped 90/year and the graduate student population was around 60.

When Dr. Peck stepped down in 1992, he left the legacy of a growing, active Department and a revitalized Chemistry Department. He had seen implementation of many of his ideas and policies throughout the Biology Division. While credit for many of the major accomplishments must be shared broadly with other administrators and foresighted individuals throughout the state, clearly the University and the State are better for the leadership of Dr. Harry D. Peck, Jr., and the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular biology owes him its very character and much of its success.

Compiled and written by John E. Wampler

Harry D. Peck, Jr. (1979) "Ten Year Self-Study," Department of Biochemistry, University of Georgia.Harry D. Peck, Jr. (various), Departmental Annual Reports

Interviews with Dr. Lars Ljungdahl, Dr. Leon Dure and Dr. Jack Payne.

Written rememberances of Milton Cormier, Jean Le Gall, Howard Gest and Jim Travis.

Memo to David Puett from William L. Williams, RE: History of the Start of the Biochemistry Department (March 2, 1993).

Letters of Dr. Lars Ljungdahl to President Charles Knapp (August 2, 1991) and Dean John J. Kozak (January 7, 1992).

M. J. Cormier, R. A. McRorie, L. S. Dure, and W. L. Williams (1964) "Proposal for Creation of a Department of Biochemistry at the University of Georgia."

The University of Georgia Research Reporter, Summer 1969, Vol. 3 (4).